A renaissance for Indian art

Click here to view original web page at www.telegraph.co.uk

There have been countless such gatherings at Jehangir Art Gallery over the years. It’s the opening of a group exhibition of new sculptures and paintings. In between posing for photographers, the artists mingle with friends, family and would-be collectors; flowing freely are tropical juice drinks, in many cases alcoholic; and, given the 35-degree heat, few of the male guests’ kurtas are buttoned right the way to the top.

A public institution founded in 1952, this is Mumbai’s most illustrious art gallery. As its secretary, Karthiayani Menon, tells me over the hubbub, “anyone who’s anyone in Indian art has showed at the Jehangir. From SH Raza to Bhupen Khakhar, all the big names have had an exhibition here: it’s a rite of passage”.

Khakhar (1934-2003), one of India’s leading artists of the 20th century, is currently the subject of a retrospective at Tate Modern in London, 50 years after he launched his career with a debut show at the Jehangir.

Though he spent most of his life in nearby Vadodara (previously known as Baroda), Khakhar was born in Mumbai and retained strong links with it throughout. Indeed, making one’s way around the city today is still, to a large extent, to enter one of his pictures. The the shoe shiners, the rickshaws, the movie posters... Khakhar’s great contribution to Indian art was to introduce to it the language of the street. Where, broadly speaking, painters in the subcontinent had struggled previously to shake off the twin influence of their own miniature tradition and imported European trends, with Khakhar Indian art went Pop. Not for nothing was he dubbed India’s David Hockney.

In between drinks, Menon shows me around the Jehangir’s lending library, intended to offer locals who seek it a grounding in art history.

As for the exhibition schedule, “We’ve got every potential slot booked between now and 2023,” she says.

Visitors to the Jehangir have always entered beneath its distinctively white and wavy awning, but the interior has been amply renovated and expanded in the years since Khakhar showed here – with four different gallery spaces now in use: a reflection not just of this institution’s growth but also of Mumbai’s own as an artistic hub.

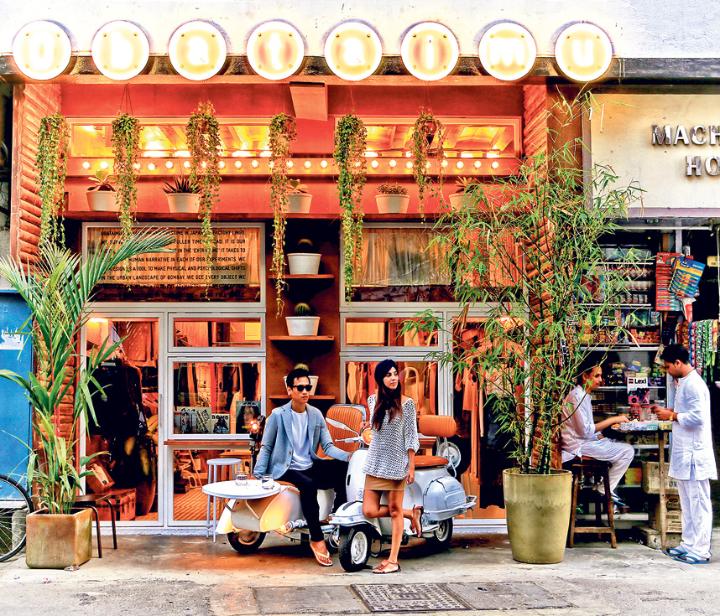

The Jehangir is located in the so-called Kala Ghoda area, in the city’s south, opposite the Prince of Wales Museum (home to a stunning collection of Gupta, Maurya and other ancient Indian sculpture that’s a must-see for even the shortest stayer in Mumbai). There has been a lot of buzz about Kala Ghoda recently: this pedestrian-friendly zone in such a car-heavy city is fast becoming a cultural nerve-centre, with a host of boutiques and restaurants popping up on its cobble lanes. Various colonial-era buildings have been restored, and dozens of smaller art galleries have opened too, with the ambition of becoming the next Jehangir.

Inspired by equivalent collaborations in London and New York, Mumbai’s galleries now also team up once a month for “Art Night”: staying open till 9.30pm on the second Thursday of every month, in a bid to get as many folks through as many doors as possible. A helpful map can downloaded at asiaartprojects.com/map or picked up participating galleries, and guided tours are also available.

“It’s a sign of how far the city has come,” says Shireen Gandhy, director of Chemould Prescott Road gallery, the final stop on many tours. “Seeing art has never been a mass pursuit in Mumbai, or in India generally, but times are definitely changing – for the better.”

Gandhy dates these changes back to the early 2000s, a time when the Indian art market experienced its first boom and since when “young, experimental, risk-taking galleries have started appearing”.

Chemould Prescott Road, a commercial gallery in a vast loft space, was opened by Gandhy’s parents in the Sixties and represented Khakhar till his death.

Emerging artists have always been the Gandhys’ priority. Nowadays that means the likes of Jitish Kallat, who’s exhibiting on the day I visit: in one set of sculptures, he uses rotis to evoke the different shapes and surfaces of the moon across the lunar month. In his time, Khakhar certainly stood out too, says Gandhy, for his treatment of gay themes, then a taboo subject in India. She remembers her mother telling her a story of Khakhar’s painting Two Men in Banaras (currently on show at Tate), when it was shown for the first time at their gallery in 1982. “A Swiss collector turned up one morning and was super interested in buying it, so he pleaded with mum to hold it for him for an hour while he got his finances together. Mum told him to calm down and not worry: because of the subject matter [a naked gay couple embracing], no Indian would dream of purchasing that painting”.

For the rest of 2016, the best place in India to see Khakhar’s work is actually in Delhi, at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), which is hosting a major display. His unabashedly loud use of colour is what strikes you at first – the crimson reds and emerald greens – before you get any sense of the street-corner barbers and other subjects he’s actually depicting.

A one-time maharaja’s palace, the NGMA is located at the heart of New Delhi. Its collection of 15,000 works offers a who’s-who of Indian art of the past two-and-half centuries – and, as you ascend from ground floor to third, a handy, chronological introduction for beginners.

The story starts in the late 18th century with the artist-travellers of Europe – Johann Zoffany, William Hodges, Thomas Daniell et al – who toured India and were inspired by its exotic landscapes and communities.

What’s interesting, as you reach the 20th century rooms, though, is how many of these names are becoming well-known worldwide. Vasudeo Gaitonde was given a retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 2014; the same city’s Metropolitan Museum is currently holding an exhibition by Nasreen Mohamedi. Throw Khakhar at Tate into the mix and you see a new-found appreciation of India’s recent artists and an increasingly globalised appreciation of the Modernists who made a difference to art history.

As for Delhi itself, the sense is of a city on the up and up. The construction of a metro, followed by hosting the Commonwealth Games in 2010 and Formula One Grand Prix since 2011, have given it a whole new cultural confidence. It also boasts the respected Delhi Art Fair every January.

“For years, Delhi was starved of culture,” says Aparajita Jain, director of the gallery, Nature Morte. “It was once simply a political capital, while Mumbai – the home of Bollywood – was always India’s arts capital. That gap is closing fast, however.”

“As the city has grown wealthier and more cosmopolitan in recent years, it has become more artistic too,” says Jain. This doesn’t just mean an increase in commercial galleries, but in not-for-profit institutions too, such as the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, set up in their own name by local millionaires. (State support for the museum sector in India has never been much to write home about.)

What Delhi doesn’t have (yet) is a Khala Ghoda equivalent, a specialised art zone. But getting around the city on rickshaw, taxi or metro is no huge trouble. Nature Morte itself can be found in the city’s centre-south and is one of its most successful galleries.

On the day I visit, it is showing shots by the photographer Gauri Gill of the Indian diaspora abroad. Are these the people responsible for most of the purchases of Indian art in recent years?

“In part. But we’re also seeing the rise of buyers within India itself, as well as the rest of Asia, as the wealth in the region grows.”

India accounted for a modest $300-million share of the $64 billion total of art sales worldwide last year (compared to the US’s $27bn and Britain’s $13.5bn). But that figure is expected to double by 2020 and, as Jain points out, “on its own terms, the Indian market is growing fast. Come back in 12 months’ time and I’m sure you’ll notice another leap forward.”

It’s interesting to think that an artistic tradition which is millennia-old is now transforming by the year. But that’s India for you: a land of endlessly fascinating contradictions.

Getting there

Cox & Kings (020 3642 0861; coxandkings.co.uk) offers a seven-day Taj tour to Delhi and Mumbai from £1,525 per person b&b, twin share. Includes BA flight from London, internal flights, transfers, three nights at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Delhi, and three at the Taj Mahal Palace, Mumbai.

Staying there

The Taj Mahal Hotel in Delhi (0091 11 2302 6162; tajhotels.com) is a centrally located five-star property.

The Taj Mahal Palace in Mumbai (0091 22 2202 3366; tajhotels.com) boasts an extensive collection of modern art.

Retrospective

You Can’t Please All, an exhibition of work by the late Bhupen Khakhar, runs at London’s Tate Modern (tate.org.uk) until November 5.

Click here to view original web page at www.telegraph.co.uk

July 11, 2016

Leave a Comment